Speculating Futures: A Conversation with Letta Shtohryn

‘The tools we work with are always somewhat alive, almost as if there’s a ghost in them subtly guiding the process.”

[RESIDENCY] Letta Shtohryn’s work had been selected for the second Realities In Transition residency which took place at iMAL – Art Center for digital cultures & technology, with the help and advice of the Belgian collective “CREW”. A perfect occasion to work on the multiple layers of realities involved in her project “Чули ? Чули”. Dark Euphoria asked her about her relationship to XR, her personal journey through it, her experience of the residency, and her favourite tools+inspirations.

Portrait: Letta Shtohryn

Dark Euphoria | Interviewer: Céline Delatte

Happy to finally e-meet you! Thanks for accepting this interview as you finished your residency on “Чули ? Чули” with the help of CREW. To begin, could you give us a quick word to introduce yourself?

Letta Shtohryn: My name is Letta Shtohryn. I’m a Ukrainian artist and a researcher living in the EU. I mainly work with XR, CGI, video narratives, post-humanism and the embodiment with machines and humans + non-humans. I find myself positioned between being a media artist and a contemporary artist. I wouldn’t want to limit it to XR alone, as my primary background lies in visual arts. I consider myself more of a visual artist who works with technology, as I also reflect on technology in my work. However, it doesn’t drive my practice; it’s not the initial catalyst for my work. Technology is employed when it’s relevant. Ultimately, I see myself as a visual artist who engages with media arts.

C.D.: Could you tell us a bit more about the project you worked on as part of your residency in iMAL, and on which aspects you had the occasion to progress with the help of CREW?

Letta Shtohryn: The project I worked on is called “Чули? Чули / Chuly? Chuly,” which in Ukrainian means “Have you heard? We’ve heard / Have you felt it? We’ve felt it.” The title suggests hearing and feeling are intertwined, which was later translated into the theme of the work, focusing on cognitive manipulation and online disinformation and their real-life consequences. I was exploring the emotional impact of cognitive manipulation—similar to what we encounter daily online with inflammatory posts and manipulative content.

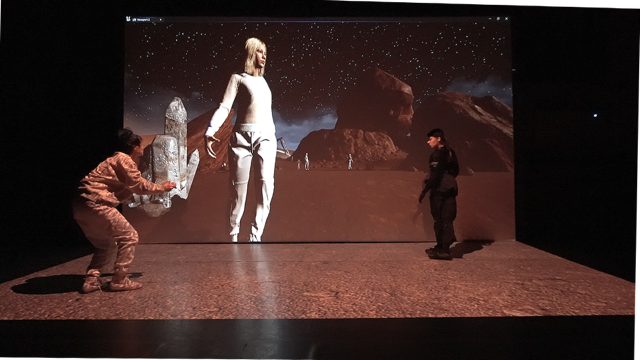

The project is both a video game and a dance performance. The main narrative that the audience hears in the work revolves around an urban legend about an encounter with giants, but the narrative that guides the player follows the mutation of stories when they are used for disinformation. In the game world, the player hears voices in different locations that project various attitudes towards the giants’ narratives—from disbelief to exaggeration, to fake authority supposedly confirmed by “researchers,” and so on.

I initially conceptualised and demoed the project in Linz at the Ars Electronica Founding Lab in autumn 2023 with Julie-Michèle Morin (dramaturg) and Junjian Wang (dancer). After the initial demo was shown to the public, I continued exploring the choreography and the calibration/uncalibration of the MoCap suits at iMAL, focusing on how these aspects depended on the dancer’s movements and the theatrical, audience, and dramaturgical elements of the work. Working with CREW was particularly beneficial, as their expertise in XR performances and audience engagement validated some of my ideas about the dramaturgy and helped me develop alterations for future audience experiences.

The work heavily centres on the narrative mutation of the original story, so we carefully considered how and when to present this original narrative. Based on this idea with CREW’s mentorship I have worked on adding additional intro and outro to the work, which has a VR/ VR on screen element in it. We decided to extend certain scenes, which led to the work mutating from its original form. Ultimately every showing of the work offers a slightly different experience, whether the difference is in the narrative itself, in the choreography or in the way the narrative is experienced by the audience.

C.D.: Next question is about the tools that you used during the residency, the more appropriate tools to build the kind of complete experience you propose with “Чули ? Чули / Chuly? Chuly”?

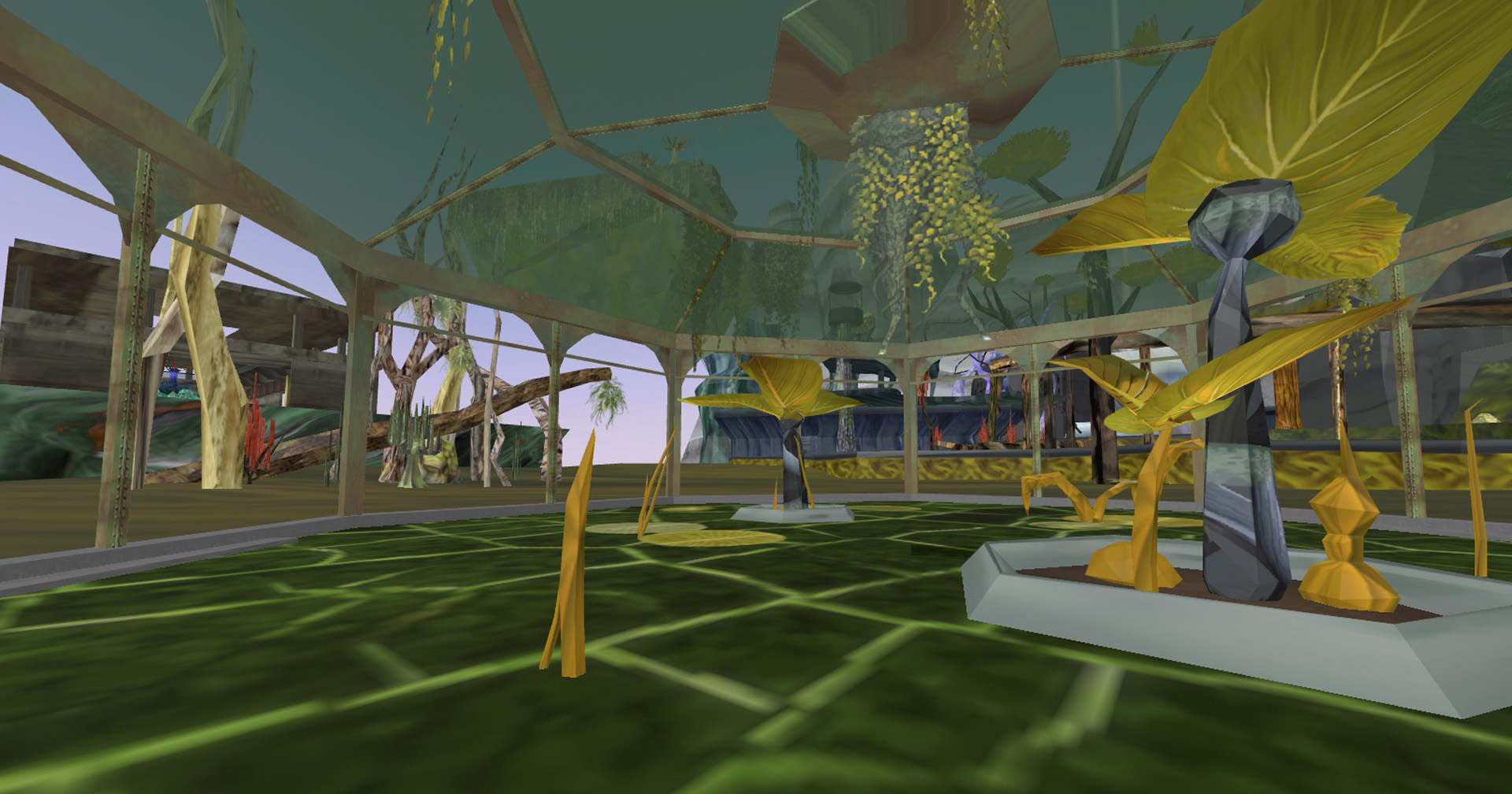

Letta Shtohryn: My tools primarily include conventional commercial CGI software and Unreal game engine. I use Unreal for world-building, camera work, interaction, and any activities within the work that can be blueprint coded. I begin with the conceptualisation of the project and then create a level map. After that, I sculpt and texture the world, building a complete environment — weather, sky, lighting rules, and so on. For example, I decide how many suns there are and what the day-night cycle will be. When technology permits, I incorporate procedurally generated natural features such as rocks and plants.

However, in this particular work, there are no procedurally generated objects because it is performed in Edit mode, live from my laptop, which outputs a video over 4K. Procedurally generated objects can destabilise the entire process by, well, crashing it. This adds an additional layer of error and unpredictability.

After the world is built, I move on to the characters. If the work is interactive, I consider who Player 1 and Player 2 are—what they look like, what clothes they wear. For this, I use Metahuman and ZBrush for additional feature sculpting. If the clothes need to be customised beyond standard options, I design and sew them in Marvelous Designer, then export to ZBrush for mesh fixing, and finally to Maya for remeshing. For texturing, I use Marmoset and Substance Painter. Once the avatars are created, I calibrate the rig to match the motion capture suit I’m using.

When all these elements are in place, the dramaturgy and dance can begin. This marks the point of liveness and performance. The motion capture data is streamed live into the Unreal Engine world, which is then displayed on a multi-projector setup. From that point, there’s a lot of back and forth—the concept, dramaturgy, and dance evolve to fit the vision, and vice versa.

In this work, the concept (bodies behind digital personas, manipulation, embodiment) and the technology feed into each other. In one part of the work the motion capture suit gains technological materiality, and through the magnetic interference in the performance space it influences and directs the choreography of the dance. The suits I use are inertial motion capture suits, which are susceptible to magnetic interference. This means that technology and metal objects in the room can interfere unpredictably with the calibrated avatar on the screen—the avatar gradually deviates from the dancer’s movements, causing a slow uncalibration.

This element of error entered the work through the suit, and I felt it aligned well with the concept. Moreover, because of the interference, the dance is always slightly different. At iMAL, dancer Marion Busetti and I worked extensively on this aspect, exploring whether we could control this uncalibration. We developed a sort of movement language that somewhat influences it, but ultimately, the suit determines how and when it will fully uncalibrate. We only managed to exert some influence on this process with the choreography we devised. I find this potential for error and imperfection quite appealing, as it subverts the audience’s expectations. The work presents a crisp, shiny, AAA game-style realism, yet gradually, the giant avatar deteriorates into a disjointed pile of limbs. This is why the technology and the concept worked together so well, guiding each other throughout the process.

Of course, these elements of error and liveness can go horribly wrong. But when everything functions as it should, that Windows doesn’t suddenly decide to update just before the performance, and the spirits of technology are on our side, the audience will experience the show we’ve intended to present.

C.D.: How did you actually meet XR?

Letta Shtoryn: Before gaining access to the tools needed to work with XR, my practice primarily involved video, imagery, and machine vision. I then moved into working with Machinima, which involves recording videos within video games. Certain video games have left as lasting an impression on me as artworks I’ve encountered in museums, so combining the two felt quite organic. Machinima was the first time I brought these elements together. In Machinima, one creates films or narratives within video games. I enjoy both the medium and its culture, though it also raises many questions about ownership, which I find quite intriguing.

The first Machinima work I created was in 2019, titled Algorithmic Oracle. In this piece, I used The Sims 3 and its somewhat random fire algorithm to recreate the event of my own house catching fire (based on true events). I would set the initial actions for the avatars and then film the outcome generated by the game. After that, without saving, I would start again. I became the camerawoman of my own house catching fire in The Sims, observing what the algorithm decided for me. I think I captured more than 100 different scenarios, but only 10 made it into the final work.

As for my expansion from Machinima to CGI and XR, I think my interest lay in immersion—the variety of worlds one could create and the idea of being in multiple places at once. I reflected on which specific types of immersion suited my work, and this led me to pursue a PhD in Media Art, with a focus on immersion. Once I had access to the necessary technology and a lab, I began experimenting. I was also deeply interested in the entanglement of the body with technology within this immersive space. These questions gradually led me to transition more towards an XR practice.

My biggest motivation came during a residency at Goldsmiths College in London in 2022, which was centred around livestreamed motion capture. I had the opportunity to work with and explore the technology. This is how one becomes involved—by having access and being able to play with it. It’s not just about thinking about technology; one actually needs to engage with it hands-on. That’s when I started working more with motion capture and began experimenting, often trying to break it.

C.D.: So “immersion” was kind of your bridge between performance and technology…

Letta Shtohryn: Yes, and the performance introduced a present and live element. With motion capture, you can use pre-recorded animations, which is nice, but the live aspect is where it truly stands out—each performance looks different every time. It’s incredibly stressful because it sometimes doesn’t work as intended, but you learn to live with the errors. That unpredictability was quite fascinating for me. The live element enhanced my interest in embodiment and immersion, and it seemed like a perfect match.

C.D.: Where do you actually find your main inspirations?

Letta Shtohryn: I’m fascinated by anything related to sci-fi (currently, I’m reading pre-moon landing sci-fi, –– “Three-Body Problem” etc.), visual art, video games (Horizon Forbidden West is my favourite at the moment), weird historical facts, and archaeology. I also have a strong interest in early modernist cinema.

It’s fascinating to see what people decide to do with innovative technological devices. There’s a certain weirdness that emerges as people experiment with everything, and eventually, these innovations become standardised. I’m not claiming technological novelty in my work; I’m simply combining relevant tools at my disposal, though I am intrigued by the unconventional uses of technology.

Since I work with speculation, I’m particularly inspired by gaps in knowledge, whether they’re current or historical—these gaps are where speculation thrives. In “Чули? Чули / Chuly? Chuly”, I collaborated with Heritage Malta to adapt into my work a 3D scanned model of a temple in Malta that’s around 5,000 years old. It’s an unusual subject: archaeological, yet tinged with science fiction due to its age and the lack of data surrounding it, which allows space for a myriad of urban legends.

I’m also fascinated by speculative futures. I once worked on a project with geologists to identify Martian lava tubes suitable for the first human habitats. My role was to visualise these concepts, and this project provided enough inspiration for my installation Life on Mars Might Not Want to Be Found (2022). That experience has now led to a project I’m currently working on—a CGI documentary about the largest meteorite in Europe that fell in Ukraine, which is questioning space heritage and its ownership.

All of these inspirations are intertwined with my lived experience and the political reality I face today as a Ukrainian artist living abroad, working with CGI while my home country is under attack both physically and cognitively by Russia and its pervasive and globally reaching disinformation machine.

C.D.: And if you would have any advice to give for an artist or creative who wants to start with XR?

Letta Shtohryn: You need access to technology, but I’d say don’t rush to buy anything. Instead, find a place where they have all the tools so you can experiment and discover for yourself what’s interesting and what you enjoy. Ideally, as a young artist, having a space where you can truly push the limits of technology—not physically break it, but explore what it can and cannot do—is invaluable. That’s where the most unusual ideas emerge. Personally, I do everything myself, which I think stems from my visual arts background: I want things to look a certain way, and I need to make them look that way. I’m willing to spend the time learning how to achieve that, even if it takes months. But also, It’s a kind of call and response—you want to create something and have it look a certain way, but when you can’t, you’re forced to ask, “Okay, what does it look like now? How can I build on this?” The tools we work with are always somewhat alive, almost as if there’s a ghost in them subtly guiding the process.

C.D.: We might call him the technologhost! (laughs). How would you define eXtended Realities and how does it actually redefine the idea of reality itself?

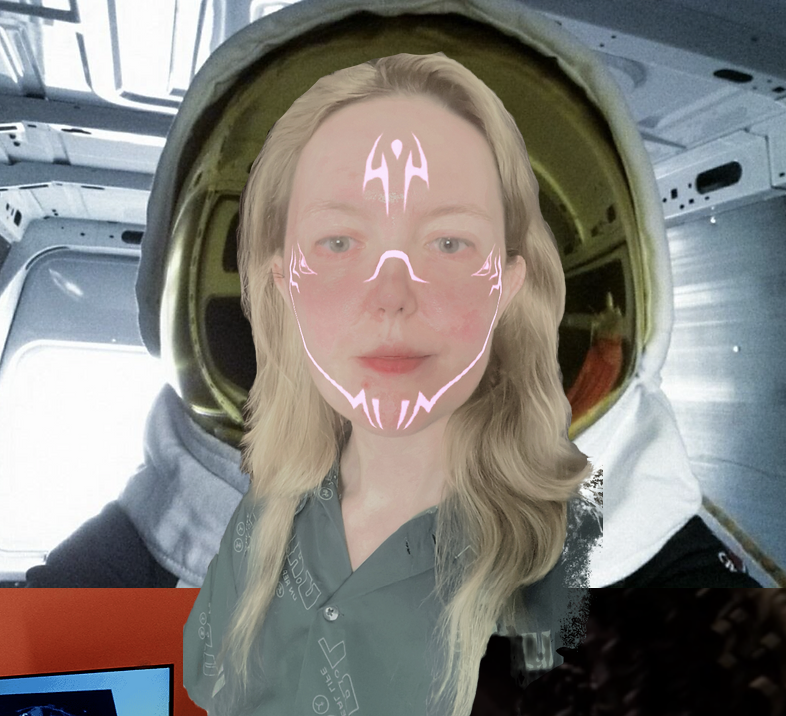

Letta Shtohryn: XR incorporates MR, AR, and VR, adding a digital experience to physical presence. As Milgram+Kishino’s famous scale and its subsequent revisions tells us: MR (mixed reality) overlays digital elements on physical space, allowing for interaction; AR (augmented reality) adds a digital layer to the physical world, enabling you to see both simultaneously; and VR, of course, locks one’s vision out of the physical space, visually and mentally transporting you to another setting. I’m particularly interested in XR experiences and settings that cannot be fully experienced in physical space alone.

As for immersion, I believe it can be found in many things. For me, VR alone isn’t quite enough because my body eventually realises it’s not actually in the setting it perceives. AR adds to what is already present, and MR introduces interaction. But immersion can exist both within XR and outside of it—it can be found in a seventeenth century panorama, a podcast, a cave painting, or a story.

I’m particularly interested in extended realities where technology enhances your physical experience. To work with motion capture, for example, I needed to see a screen of a certain size displaying an avatar guided by the motion capture. This setup helps in working with the body and its technological extensions simultaneously. I think many people define XR differently today, but for me, it’s definitely something that enhances physical reality—using technology as an addition to it. Without this technological layer, the experience of physical reality would not be the same.

C.D. : And to conclude, where do you think XR is headed and where would you want it to go?

Letta Shtohryn: I want to move away from defining XR solely as VR experiences, as it’s often used in contexts where it’s not necessary. Extended reality is also a form of immersion. Not all immersions are extended reality, and not all extended realities are immersive, but I believe we should broaden the tools we use for extended reality and combine them with those used in theatre, stagecraft, visual arts, and storytelling—even those that are quite analogue. That’s the direction I’d like to see it take, and I think it’s already beginning to expand in that way. There are initiatives like this residency, as well as numerous programmes, grants, and projects aimed at making XR something more than just a single type of technology—something broader and more inclusive of other disciplines. Perhaps it’s just wishful thinking, or maybe it’s the bubble I’m in, but I’d like to see it delay standardisation and evolve into something weirder.

C. D.: Weird-R is the new XR! Thanks a lot Letta!

Interview Letta Shtohryn of by Céline Delatte, Communications Officer for RIT’s partner Dark Euphoria as part of the iMAL artistic residency in Brussel.